Pete Buttigieg is leading at 63 percent. Andrew Yang came in second at 46 percent. And Elizabeth Warren looks like she’s in trouble with 0 percent.

These aren’t poll numbers for the U.S. 2020 Democratic presidential contest. Instead, they reflect which candidates were able to consistently land in Gmail’s primary inbox in a simple test.

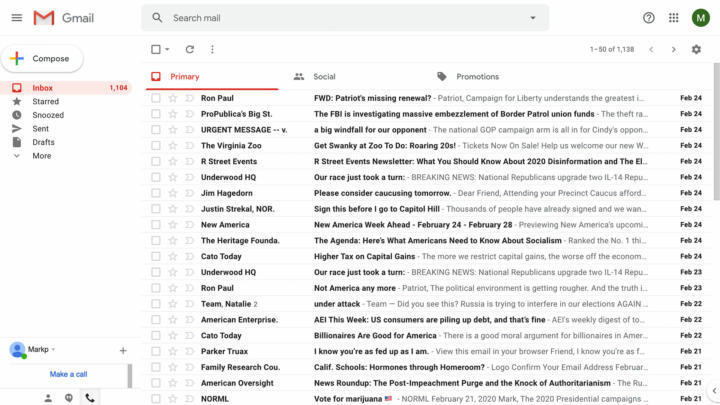

The Markup set up a new Gmail account to find out how the company filters political email from candidates, think tanks, advocacy groups, and nonprofits.

We found that few of the emails we’d signed up to receive—11 percent—made it to the primary inbox, the first one a user sees when opening Gmail and the one the company says is “for the mail you really, really want.”

Show Your WorkGoogle the Giant

How We Examined Gmail’s Treatment of Political Emails

We conducted an experiment with a new email address to try to figure out how Gmail's sorting algorithm worked without user input

Half of all emails landed in a tab called “promotions,” which Gmail says is for “deals, offers, and other marketing emails.” Gmail sent another 40 percent to spam.

For political causes and candidates, who get a significant amount of their donations through email, having their messages diverted into less-visible tabs or spam can have profound effects.

“The fact that Gmail has so much control over our democracy and what happens and who raises money is frightening,” said Kenneth Pennington, a consultant who worked on Beto O’Rourke’s digital campaign.

“It’s scary that if Gmail changes their algorithms,” he added, “they’d have the power to impact our election.”

It’s well known that Facebook and Twitter curate which posts people see through the news feed, highlighting some while others are scarcely shown. What’s received less attention is how email has also become an algorithmically curated and monetized platform—essentially another feed—and the effect that can have. Some nonprofits and political causes said inbox curation is reducing donations and petition signatures.

Google communications manager Katie Wattie said in an email that the categories “help users organize their email.”

“Mail classifications automatically adjust to match users’ preferences and actions,” she said. “Users really like the tab organization.”

Gmail enables the tabs by default, but they can be disabled. Wattie declined to say whether most users keep the tabs, but an email deliverability firm said about 34 percent of respondents to a 2016 survey said they use them.

The tabs also serve another purpose: ad inventory. While Gmail does not sell ads in the primary inbox, advertisers can pay for top placement in the social and promotions tabs in free accounts.

Which Presidential Candidates’ Emails Landed in Gmail’s Primary Inbox?

Some fear that, as a result, Gmail has the same conflict of interest that exists on social networks: If the platforms make it too easy to reach people for free, no one will buy ads.

“The worry is that they want to basically turn Gmail into a Facebook-style news feed where you have to pay for placement in the inbox,” said Ryan Alexander, a Democratic digital consultant.

Wattie, the Google spokesperson, replied: “What you describe is not on our roadmap for Gmail.”

Gmail isn’t the only email provider offering sophisticated inbox curation. The premium $30-a-month email provider Superhuman sorts messages into “important” and “other,” while Microsoft’s Outlook sorts messages for its “focused inbox.” Outlook and Yahoo also sell ads in their inboxes in free accounts.

But with 1.5 billion active email addresses and an estimated 27.8 percent market share, Gmail’s increasingly algorithmic inbox sorting has an outsized impact.

Nida Hasan, the director of Change.org in India, said she discovered in the spring of 2018 that the percentage of Gmail users opening her company’s emails had suddenly plummeted around the world, stalling petitions. In India, 90 percent of Change.org’s users are on Gmail, she said.

“There were a lot of really good campaigns which could not be mobilized or were stuck at a couple thousand signatures,” Hasan said.

Employees tested their own Gmail accounts and found that Gmail was sending Change.org emails to the promotions tab—even “forgot password” messages were winding up there.

A coalition of eight progressive advocacy groups in the U.S. noticed a similar change at about the same time and said it suppressed donations and petition signatures. We reviewed email data provided by Democracy for America, CREDO Action and SumOfUs and found their Gmail open rates did drop that spring, by about 50 percent compared with email sent to subscribers using other email providers.

“We believe that our ability to inform and engage the public in political action, which we believe is fundamental to a healthy democracy, is being impeded,” the coalition wrote in a letter to Google in November 2018.

We believe that our ability to inform and engage the public in political action, which we believe is fundamental to a healthy democracy, is being impeded.

Coalition of eight political action groups

During a phone conversation the following month, a Gmail official offered them a suggestion to get more eyeballs on their emails: “You’re not precluded from buying an ad in the promotions tab, or offering a deal,” said Lee Carosi Dunn, who at the time led election sales, political outreach and policy for Google, according to notes taken by one person on the call. “Your type of users may be looking for deals too, some deal that involves fund-raising or engagement.”

“We were appalled to hear that,” said Robert Cruickshank, campaign director at Demand Progress, who was on the call. “We don’t want to sound like marketing, because we’re not marketers. We’re asking people to call Congress.”

Wattie, the Google spokesperson, did not respond directly to questions about the call but rather wrote in an email that Gmail has not allowed “political content” in ads since 2016 and that those would include issue advocacy and fund-raising.

To test how Gmail treats political email, we opened a new Gmail account using a new phone number and Tor, an anonymizing browser, to avoid sending signals about political leanings based on previous web activity. Google says Gmail categorization is personalized, meaning user activity can affect where an individual’s emails are delivered.

We signed up for the email lists of 16 presidential candidates, both Democrats and Republicans. President Donald Trump’s campaign never sent us any emails.

We also signed up for congressional candidates in competitive races, and advocacy groups, think tanks, and nonprofits from across the political spectrum.

In four months, we received more than 5,000 emails from 171 groups. Much of the email sought donations. Some senders were unrelenting—at times sending more than one email a day. Nearly half of all groups and campaigns never got a single email into the primary inbox.

Presidential candidates’ emails were less likely to end up in the primary inbox than the rest of the email we signed up for: Only 6 percent of presidential candidates’ emails appeared there compared with 9 percent of other political and advocacy mail, on average.

When O’Rourke announced the end of his campaign, Gmail sent the message to spam.

Most often, presidential candidates’ emails wound up in the promotions tab in our test—90 percent of the time for some of them. Pennington, the consultant who worked on O’Rourke’s digital campaign, said the campaign’s internal data showed a lower spam rate than we found in our test.

“We are aware that emails go to Gmail’s promotions tab and we are not concerned about our ability to communicate with supporters,” said an email from Mike Casca, Bernie Sanders’s communications director.

Former campaign workers for O’Rourke, Yang, Kamala Harris and Joe Walsh also said they aren’t concerned about emails going to the promotions tab. Other candidates didn’t respond to requests for comment or couldn’t be reached.

Even emails sent by members of Congress through official House.gov addresses, which by law cannot be used for campaigning, were diverted to the promotions tab 25 percent of the time.

In marketing materials, Gmail gives straightforward examples of what kinds of emails belong in the promotions tab: “50% off Kayaking Adventure,” “$20 Off Membership,” “7 Must-Try Romantic Restaurants.”

But in our tests, the distinctions between emails that wound up in the folder and those that went to the primary inbox were less consistent.

An email with the subject line “NEW! Hoodies, sweatshirts, beanies” from BernieStore2020 went to promotions, but another announcing “So many new T-shirts! Grab yours today” from Yang2020 Merch went to the primary inbox.

A heartfelt obituary for senior fellow Michael Martin Uhlmann from the conservative think tank Claremont Institute, which did not include any calls to action, went to promotions. So did signup confirmation emails for the Texas Young Republicans and New York Young Republican Club.

Some political organizers and advocates say they are frustrated by Gmail’s categorization and questioned what political emails have to do with sales, as the “promotions” name implies.

Gavin Wax, president of the New York Young Republican Club, put it this way: “It’s just a step up above spam.”