For most of the past four years, Chantel Jones lived in a homeless shelter on Los Angeles’s skid row, hating the danger, noise, and confinement: “You feel like you’re in jail, but you’re not in jail,” she recalled.

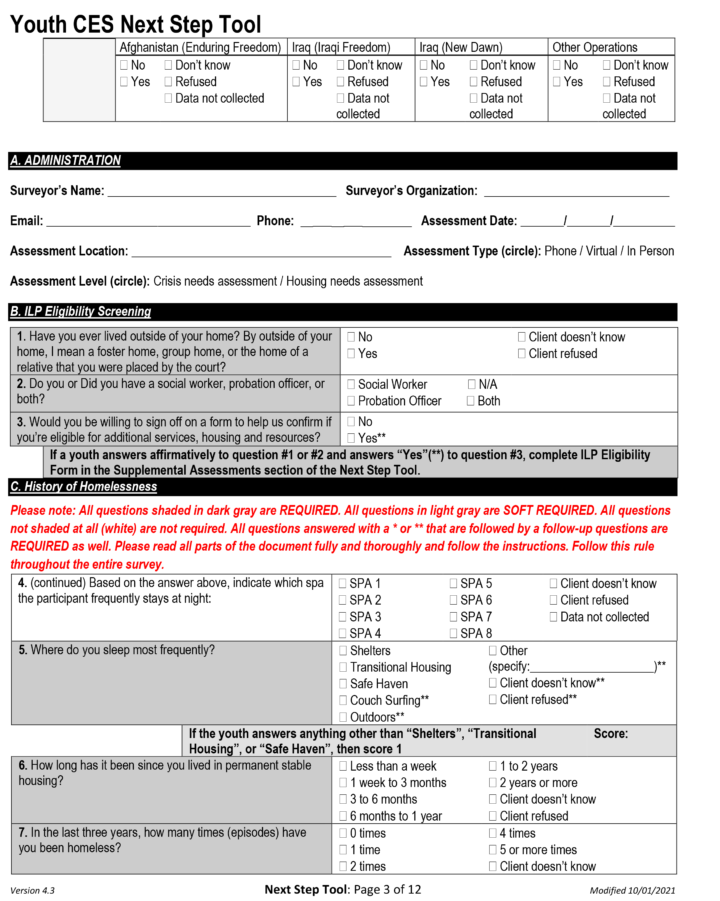

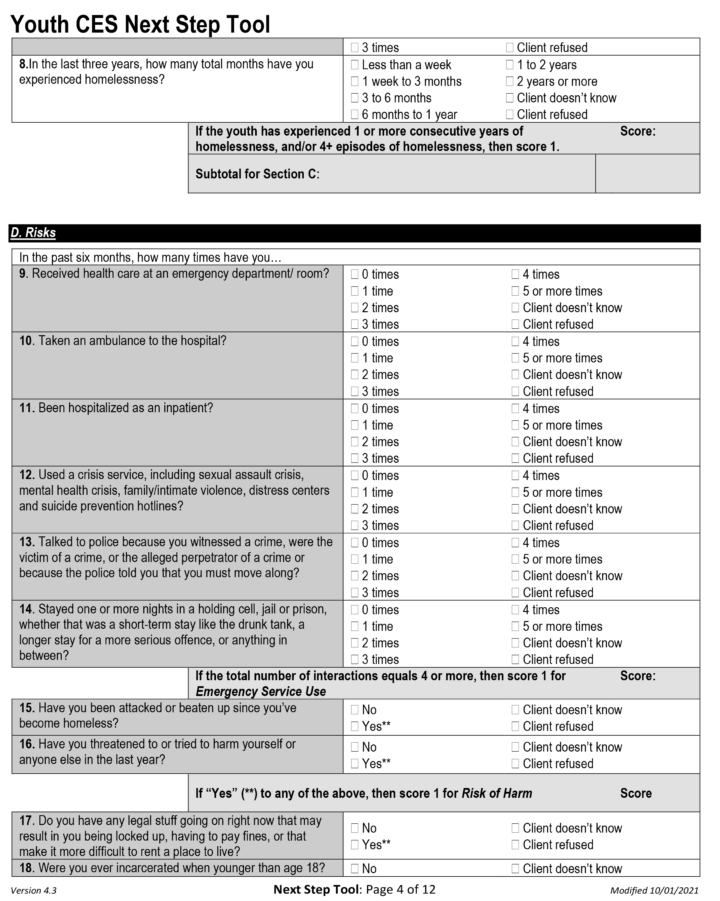

Like tens of thousands of other people dealing with homelessness in Los Angeles, Jones, who is Black, entered the housing system through an intake survey administered by a case manager. She was asked several intensely personal questions about her history, like whether she used drugs or talked to the police after witnessing a crime.

Her responses, solicited to measure her “vulnerability,” were scored, added up, and used to help determine whether Jones would qualify for subsidized permanent housing. This scoring system is called the Vulnerability Index-Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool, or VI‑SPDAT.

When Jones discovered that she had scored too low to get placed in housing, she said she kept asking the case manager for an explanation. “He didn’t know,” she said.

An investigation by The Markup has found that Jones’s case fits a pattern. An analysis of more than 130,000 VI‑SPDAT surveys taken in the Los Angeles area as far back as 2016 found that White people received scores considered “high acuity”—or most in need—more often than Black people, and that gap persisted year over year.

The disparity is particularly stark among those who took a variation of the survey designed for people under 25. In 2021, 67 percent of unhoused White young adults scored enough to be in the highest priority group, compared with 56 percent of Latino young adults and 46 percent of Black young adults.

Among people 25 and older, smaller, but similarly persistent, disparities favored White adults. In 2021, 39 percent of White adults were placed in the highest vulnerability group compared with 33 percent of Black adults and 35 percent of Latino adults.

Show Your WorkInvestigation

How We Investigated L.A.’s Homelessness Scoring System

Year after year, White people have been rated highly “vulnerable” more often than Black people

Longtime observers of Los Angeles’s approach to homelessness say scoring disparities in the system are alarming and may mean Black unhoused people are getting less help than they should. The findings come at a time when the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA), the independent joint city and county agency responsible for coordinating homelessness services in Los Angeles, plans to stop using the tool entirely, after a research team partnering with the agency found the tool had “the potential to advantage certain racial groups over others.” But with no replacement yet available, the agency continues to rely on it.

Despite their lower vulnerability scores, Black people were, according to a 2018 LAHSA report, slightly overrepresented among those in LAHSA’s permanent housing programs, compared to the proportion of Black people experiencing homelessness. (The opposite was true for Latino people, who were slightly underrepresented.) People can go outside the matching system and find housing themselves: In data provided to The Markup by LAHSA, a person may be counted as “permanently housed” if they “self-resolve” by finding housing on their own, just as if they’d been matched and placed, according to LAHSA.

The data didn’t distinguish between those housing outcomes, making it difficult to understand the exact relationship between a person’s score and whether that person ultimately is matched to housing. But those who work with the system insist the score is a major component.

“All things being equal on eligibility, the top score is going to get the offer,” said Marc Tousignant, who studies homelessness issues in Los Angeles as senior program director for vulnerable populations at Enterprise Community Partners, a national nonprofit.

The vulnerability assessments have long been mysterious to the people they are designed to help. Neither Jones nor others caught in the epidemic of homelessness in Los Angeles are supposed to be told that they’re being scored. Case managers administering the survey are instructed to not reveal the process so people aren’t alienated by being referred to as numbers. “DO NOT VOLUNTEER THE SCORE OR THE SCORING PROCESS,” a 35-page information packet states.

Black people tend to receive lower vulnerability scores despite their overrepresentation in Los Angeles’s unhoused population. In 2022, Black people made up about 9 percent of Los Angeles County’s population but 30 percent of the more than 65,000 people experiencing homelessness. The 2018 report from LAHSA found that “structural racism, discrimination, and implicit bias” played significant roles in the gap.

Story Recipes

Journalists: Investigate Homeless Vulnerability Scoring in Your City

The survey we investigated was also used in dozens of other cities and counties, according to its creators. Here are our tips for looking into it

LAHSA spokesperson Christopher Yee said in a written statement that the agency was aware of “troubling racial disparities” in its assessment system and has partnered with outside researchers from the University of Southern California and the University of California, Los Angeles, to address those disparities by developing a new assessment tool.

“Overall, the Project identified the need for both a new tool and a new approach to how housing resources are administered, which LAHSA and our partners are excited to share more about in the coming months,” Yee said.

A further statement, from LAHSA spokesperson Ahmad Chapman, said the agency has continued to use its current system to match adults to permanent housing because the need is so great. The statement said LAHSA “has done a decent job of connecting various racial groups experiencing homelessness to permanent supportive housing” but recognizes “significant room for improvement” in reducing racial disparities.

Advocates have questioned for years whether the scoring system accurately reflects the vulnerabilities of Black people. But the evidence until now has been largely anecdotal. For its analysis, The Markup obtained scoring data through public records requests from LAHSA, which collects surveys from a sprawling network of nonprofits that administer them.

The survey LAHSA oversees plays a pivotal role in allocating scarce resources. The results can influence whether a person is matched quickly to a permanent home, spends years waiting for help, or doesn’t get a home at all. But they are not the only factor. For example, a building may open that accepts only tenants who are veterans over 55 years old, or only those with a certain medical condition. Case managers also have opportunities to press for housing for people when they feel the survey score isn’t properly reflecting the direness of their situation.

LAHSA is required to use some kind of prioritization system to become eligible for certain federal housing funds under rules established by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The tool it uses for adults was created in 2013 by two consulting groups. As of 2015, the VI‑SPDAT had been adopted by dozens of communities across the U.S.

But in the years following, the evidence that the tool is poor at predicting outcomes and disproportionately harms Black people has added up. Dennis Culhane, a professor of social policy at the University of Pennsylvania, said his research and that of his colleagues in the field has found that the VI‑SPDAT is bad at predicting which people experiencing homelessness, without help, will die in the near future or be incarcerated or hospitalized.

“The VI-SPDAT was like flipping a coin in terms of the predictability,” Culhane said.

He said that, perhaps because of stigmatizing questions, Black people are more hesitant to describe their history with doctors or police, leading to lower scores.

From Survey to Housing

The 35-page packet case managers use to determine people’s score has dozens of questions that must be answered. The questions on the survey ask whether the person took an ambulance recently or talked to the police after witnessing a crime. If so, the survey asks how many times.

If either happened four or more times in the past six months, that’s one point added on the 17-point scale.

The survey asks whether the person has been beaten up recently, takes “risky” actions like sharing needles, or owes someone money. Other questions focus on emotional fulfillment, or on social lives. “Do you have planned activities, other than just surviving, that make you feel happy and fulfilled?” one asks.

The points are tallied into the “vulnerability,” or as it’s otherwise known in the field, the “acuity” score. The higher the person’s vulnerability, as measured by the survey, the higher priority they’re supposed to be for permanent housing. When a new building opens or a vacancy otherwise arises, designated “matchers” are responsible for finding the most qualified unhoused clients for the space. They make this choice based on any criteria particular to the building as well as the vulnerability scores.

In L.A., some have questioned whether the tool and its simple 0–17 scores can meet the diverse challenges of a sprawling program that shelters tens of thousands of people. Hazel Lopez, director of Coordinated Entry Systems with nonprofit housing services provider The People Concern, gave the example of an unhoused, terminally ill cancer patient her organization worked with. The person hadn’t been without housing for that long and thus might not have received a high vulnerability score, but clearly needed help immediately. In those situations, she said, nonprofit services work around the scoring system, advocating directly with LAHSA to try obtain help and telling the agency, “This might be one of those anomalies where the assessment isn’t capturing this person’s situation, but we know that they’re a little more vulnerable than most.”

USC professor Eric Rice is part of the team studying how to make LAHSA’s system more equitable, including testing a tool that more accurately predicts outcomes and potentially changes how housing is allocated. “We’re talking hundreds, if not thousands, of people who could be helped who are maybe being overlooked,” Rice said.

Evelin Montoya and Berenice Hernandez-Rodriguez are matchers working for The People Concern in Los Angeles’s Service Planning Area Four, an area that includes skid row. They say people with higher scores are generally placed first in line for housing offers. “We filter our 17s, our 16s, and 15s—that’s where we go first,” Montoya said. If a high-scoring person doesn’t meet the requirements for a particular vacancy, such as being a veteran or being over 65 years old, the matchers go down the list, finding the next person who fits a building’s criteria.

The case manager’s personal judgment can come into play, they say, and housing organizations can request an exception directly from the housing services authority when they feel a survey score is not accurate.

Individual case managers will also vary in how they score and place people. Sometimes, Montoya said, a case manager may have just started their first social services job a week before—“no training, no guidance”—and not be able to administer the survey properly.

Another might try to game the system in their clients’ favor. “Sometimes we have case managers that are notorious for everybody on their caseload being a 17,” Montoya said, “because they also know that higher acuity equals housing.”

Eroding Confidence in Scores

As Los Angeles looks at testing a new scoring system, the two groups that created the vulnerability survey are backing away from it.

In 2016, one of those groups, Community Solutions, warned in a blog post of “the Robot Trap,” the false notion that the tool could “eliminate the need for human judgment in housing decisions.” Community Solutions’ Beth Sandor, who wrote that post, said that a score is ideally “just one piece of information being brought into the room,” and one that is “not the decision-maker.”

Some researchers have questioned whether the scoring system is an effective way to deal with homelessness even when only used to inform a human decision. One 2018 study suggested the tool was a relatively poor way to predict who would fall back into homelessness, concluding that “total scores did not significantly predict risk of return to homeless service.”

A 2019 report from C4 Innovations, a consultancy group that works on homelessness services, examined similar systems in four counties across three states. The report found that people of color received statistically significantly lower scores than White people, and that race was a predictor of how high a score an individual received.

By 2020, the other group behind the tool was also in retreat. That group, OrgCode, announced that it would phase out support for the current survey approach, citing in part the questions about racial disparities.

Rice says the real problem is the shortage of housing that forces officials to need a ranking system at all.

“I think that in some ways these vulnerability tools that I’m working on trying to improve are a function of a failed system where we don’t have enough resources dedicated to solving the problem,” he said.

There are remedies for someone with a low score. People experiencing homelessness who are aware of the scores and concerned that theirs is not high enough can request that a case manager survey them again, and LAHSA provides guidance on exactly how the score should be reassessed. The People Concern recommends that people request new scores as their circumstances change, so case managers can assess whether they’ll go up higher on the vulnerability scale.

Chantel Jones said she didn’t think much about racial disparities when she was going through the system in Los Angeles. She was just trying to figure out how to get into permanent housing. After a couple of years in the shelter, she connected with a case manager from The People Concern who administered the survey to her again. This time, trusting this case manager more than she had her first one, she opened up and revealed more about her drinking and mental-health issues.

She thus appeared more “vulnerable” and scored higher. When a new building opened up about a year later, she moved into a studio apartment. She had support services in the building when she needed them, and the first few months went well.

She relearned some skills, like how to shop at the grocery store after years of eating fast food. She called her sister for help with putting together chicken fettuccine. “I’ve gotta do baby steps right now,” she said.

And she was still dealing with anger over the past few years of living through a “circus,” she said.

“Don’t think for a minute it was easy for me to get to where I’m at,” Jones said. “Because it wasn’t.”

This story was copublished with the Los Angeles Times. Sign up for its newsletters here.